Apartheid is the separate-existence economic and social system that existed in South Africa officially from 1948 to 1994. Although the etymology of the word itself is rooted in the Afrikaans language of South Africa, meaning “separateness,” and refers specifically to the series of laws made in the country to the disfavour of the black population, the word has been used loosely by the infamous architect of the practice, Verwoerd, in describing the Israeli occupation of Palestine. Due to the evils of apartheid against the black population of South Africa, Nigeria from its inception had taken a stand against it.

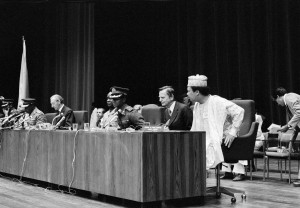

In 1960, 69 blacks were killed when many refused to carry passes that was required by a 1951 law to step outside one of the four homelands, Sharpeville, beyond which they have limited rights. These homelands had been created within South Africa to be regulated by the racist National Party dominated government, effectively making the blacks aliens in the larger part of their own country. The newly independent Nigeria, eager to take up the leadership role in Africa had provided direct financial aid to the anti-Apartheid African National Congress. Although the Nigerian anti-Apartheid posture during Tafawa Balewa’s administration was borne out of its morality, or lack thereof, many more rationale were devised by subsequent Nigerian leaders, especially after the Biafran War. In the war, the participation of the Apartheid South African government fed the somewhat needed notion by Nigeria- that it was not just serving an external interest but also protecting itself by opposing South Africa. “In opposing racism in South Africa,’ Head of State, Gowon, said at the September 1970 OAU summit in Addis Ababa, ‘we are sewing the cause of our own freedom and independence.”

Nigeria’s response

In 1974, a decree was passed making the Afrikaans language a medium of communication in school alongside the English language on a 50-50 basis. Public resentment grew, as Afrikaans was seen by the blacks as a medium of oppression. Demonstrations of June 1976 against the decree in Soweto turned violent and hundreds of school pupils were killed by the police. By this time, tension had run high and Nigerian diplomats had started worrying about the expansion of South African military capabilities. Though the Nigerian GDP per capital was barely half that of South Africa’s an arms race was not ruled out by Lagos. Nigeria in the late 1970s applied pressure indirectly on the apartheid regime by assisting liberation movement, and aiding countries sharing borders with South Africa, and by propaganda and diplomacy. Offices of liberation movements opened in Lagos, as military training and scholarships were offered for study in Nigerian institutions. Individuals whose passports had been seized were issued Nigerian passports to enable them travel. The external service of the Federal Radio Corporation broadcasted the evils of apartheid to South African audience regularly until it was jammed by South African government from reaching its citizens. Consequent of a passionate call by Nigeria’s External Affairs Minister, Joseph Garba, for the support of “brothers and sisters” in South Africa, the South Africa Relief Fund was instituted, recording overwhelming response within a short period, mostly through public servants who parted with a fraction of their salaries. Historian, Olajide Aluko discussed how Nigeria’s economic, military, and political capability to make South Africa comply with her objectives was very limited. Nigeria outdid other countries of the world, nevertheless, spending according to the South African Institute of International Affairs over $61 billion to support the end of apartheid from 1960 to 1994.

At the world stage Nigeria provided unequalled leadership in mobilizing international opinion against apartheid. In 1979, Nigeria’s foreign minister, Henry Adefowope called on the United Nations General Assembly to impose sanctions against apartheid. The British in this effort proved a hard nut to crack, but the military government of Olusegun Obasanjo made a statement against it with the nationalization of the British Petroleum and the movement of Nigerian foreign reserve from the pound sterling. Finally, the Commonwealth Heads of Government in 1985 declared that the system of apartheid must be dismantled, a position which was remarkably in variance with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s belief that it should only be reformed. The government of De Klerk, succeeding the staunchly conservative government of Botha, which had refused negotiation initiatives for the termination of apartheid supervised a transition program which brought in majority rule of Nelson Mandela in 1994.