The Hausa according to Onwubiko (1967:71) are “people who lived between the Kanuri in the East and Songhai in the West and Niger Benue junction to the desert south of Agades”. This assertion implies that the Hausa are found in West African countries like: Ghana, Niger Republic and Nigeria where they are found in the northern part of the country: Kano, Katsina, Sokoto and Bauchi States. Alkali (1987) derives from the Hausa phrase: “hausa” meaning “ride a cow”. On the other hand, Onwubiko (1967) argues that the word refers more to the language than to the people because the Hausa are not of one tribe (ethnic group). “They originated from the mingling of different tribal and racial groups of Negro farmers and nomadic Berbers from the desert.” The peoples, Onwubiko (1967) adds “are moulded into a nation by the possession of a common culture”. This assertion implies that the common denominator that unites various ethnic groups which are moulded into a nation is language i.e. Hausa. This is achieved by the attitude of the Hausa that BirmaSawa in Lemster (1984:12) points out that “they (the Hausa people) influence the community they come in contact to learn and adopt their language and culture”. Thus, Hausa has incorporated in the past various peripheral or mobile ethnic groups. Hausa is still incorporating, as people are becoming Hausa by virtue of their language acquisition (See Adamu (1970) Salomone (1975) and Mohammed (1990). Presently, Hausa is used as urban lingua franca in: a) endoglotic cities such as: Kano, Katsina, Daura, Jigawa and Sokoto and b) exoglotic cities like: Jos, Mina, Ilorin and Maiduguri etc. The Hausa States are between the rivers Niger and Benue. The language i.e. Hausa is widely spoken in the northern part of Nigeria as: “Mother Tongue, other Tongue and further Tongue” (cf. Brann (1980)). The language i.e. Hausa is officially accepted for the use as co-official language with English in the northern Houses of Assembly.

According to Greenberg (1970), Hausa belongs to Afro-Asiatic phylum. This assertion is supported by Newman’s (1977) who adds that it belongs to West Chadic. Bagery (1934) classifies Hausa into two dialects:

- a) the Sokoto dialect and

- b) the Kano dialect.

He observes further that Katsina, Zaria and Gobir belong to west dialect i.e. Sokoto dialect while Hadeja and Katsina belong to the east dialect i.e. the Kano dialect. Ahmad and Daura (1970) argue that there are two varieties of Hausa:

- a) the modern Hausa which is greatly influenced by English literature and culture and

- b) the classical Hausa which is greatly influenced by Arabic literature and culture.

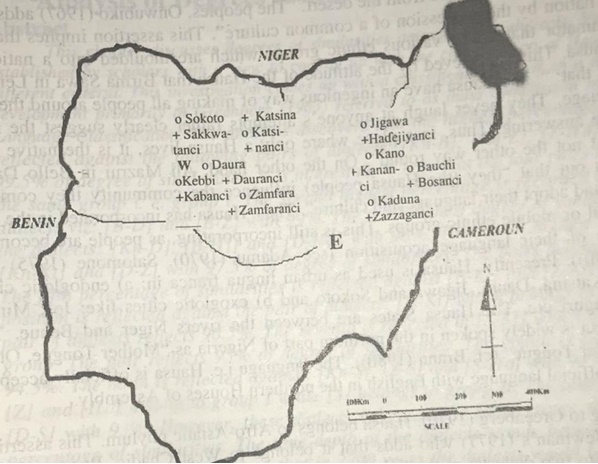

This assertion affirms the early contact of the Hausa with the Arabs which dates back to the time of the trans-Saharan trade. Ahmad and Daura (op. cit.) further identify seven dialects of Hausa: a) Kananci (Kn), b) Sakkwatanci (S), c) Zazzaganci (Z), d) Katsinanci (Kt), e) Dauranci (D), f) Hadefiyanci (Hd) and g) Bausanci (B) (see map. Muhammad (SD) identifies six dialects which are classified into two major groups: the eastern and the western groups while Dogo (1977) identifies three: the east Hausa, the west Hausa and pidgin Hausa which is spoken in the middle belt region i.e. southern Zaria and Southern Bauchi. The middle belt may include: Nassarawa, Plateau and Benue etc. that is when the recent “polito-religious” definition of the middle belt is discarded based on sentiments. Kananci is the dialect of Kano State while Katsinanci is spoken in Katsina State. Sakkwatanci is spoken in Sokoto, Zamfara and Kebbi States though; there is a sub-division within Sakkwatanci which yields Zamfaranci in Zamfara State and Kabanci in Kebbi State. Bausanci is spoken in Bauchi while Zazzaganci in Zaria Emirate in Kaduna State. Dauranci is spoken in Katsina State and Hadefianci in Jigawa State.

Hausa dialects

Various opinions were established by scholars with a view to coming up with the classification of Hausa dialects based on different criteria. This investigation comes with a classification based on a theory which owes its development primarily to Greenberg (1963) referred to as mass comparison in his Methodology of Language Classification. The analysis discovers that the highest percentages of similarities are reflected against the following pairs of dialects: [Kn-B], [Kn-Z], [Z-Hd] and [Kn-Hd] with 99.5% of degrees of similarities. It is interesting to note that the four pairs of dialects belong to the same group i.e. group 1. The second highest percentage is recorded against two pairs of dialect viz: [B-D] and [B-Z] with 99%. The third highest degree of similarities is reflected in the dialects: [Kn-D], [B-H] and [D-Hd] with 98%. The fourth highest is reflected against [Kn-Kt] and [D-Z] with 97.5% of degree of similarities. The pairs belong to different groups. The fifth percentage of similarities is reflected against [B-Kt] and [Z-Kt] with 97%. The sixth position is reflected against the pair of dialects: [D-Kt] which belongs to the same group. The pair of dialects reflects 96.5%. The seventh is reflected in [S-Kt] which also belongs to the same group. The pair reflects 95% of degree of similarities. The eight is reflected in [B-S] with 94.5%. The ninth is reflected against: [Kn-S], [Z-S] and [S-Hd] with 94%. The dialects: [Kn], [Z] and [Hd] belongs to group I while [S] belongs to group II. The tenth is reflected against: [D-S] with 93%. However, these dialects belong to the same group; they reflect the lowest percentage of similarities. The time depth of the dialects stands between 27 and 405 years.

From the foregoing, it is deduced that in 2700 years the dialects would be completely different languages within the same family if the pace separation is constant. The situation is subject to:

- a) the attitude of the speakers towards intra/inter-group relationships and

- b) the distance between the speakers.

From various degrees of similarities obtained, it is deduced that the highest percentage of similarities is reflected against the following pairs of dialects: (Kn-B), (Kn-Z), (Z-Hd) and (Kn-Hd) with 99.5% of degree of similarities. It is interesting to note that the four pairs of dialects belong to the same group i.e. group I. The second highest degree of similarities is reflected in: (B-D) and (B-Z) with 99%. Here, we observe that the pair of dialects: (B-Z) belongs to group I. the pair of dialects does not inflect the highest degree of similarities as observed in the dialects mentioned above. The dialect (D) belongs to group II but it reflects a high degree of similarities with a dialect i.e. (B) which belongs to group I. The third highest degree of similarities is reflected in the pairs of dialects: (Kn-D), (B-Hd) and (D-Hd) with 98%. In this case, we observe that the pairs of dialects: (Kn-D) and (D-Hd) belong to different groups but the pair: (B-Hd) belongs to group I but does not reflect the highest degree of similarities as observed the first and second sets of dialects. The fourth highest is reflected against: (Kn-Kt) and (D-Z) with 97.5% of degree of similarities. The pairs belong to different groups. The fifth percentage of similarities is reflected against (B-Kt) and (Z-Kt) with 97% the dialects: (B) and (Z) belong to group I while (Kt) belong to group II. The sixth position is reflected against the pair of dialects: (D-Kt) which belongs to the same group. The pair of dialects reflects 96.5% of degree of similarities. He eighth is reflected in (B-S) with 94.5%. The ninth is reflected in: (Kn-S), (Z-S) and (S-Hd) with 94% the dialects: (Kn), (Z) and (Hd) belongs to group I while (S) belongs to group II. The tenth is reflected in (D-S) with 93%. Though these dialects belong to the same group, they reflect the lowest percentage of similarities. The time depth of the dialects ranges from 27 to 405 years. From the various time depths of the dialects, we deduce that in 2700 years the dialect would be completely different languages within the same family if the separation were constant.

Investigation observes that the percentage of similarities varies according to:

- a) the distance between the dialects and/or

- b) the degree of conservativeness of the speakers of any given dialect (s).

For instance, when the distance between the dialects is short, there is high tendency of a high degree of percentage of similarities among any pair (s) of dialects as the case of (Kn-B), (Kn-Hd), (Kn-Z) and (Z-Hd). On the contrary, when the distance is long as the case of (Kn-S), (B-S), (D-S), (Z-S) and (S-Hd), the tendency is that the pairs of dialects reflect a low percentage of similarities. As said earlier, the attitude of the speakers contributes to the degree of dissimilarities this is because of linguistic forms are used for identification to a particular area.

Investigation identifies two groups of Hausa dialects:

- a) the eastern group which comprises (Kn, S, Hd and Z) and

- b) the western group which comprises (S, Kt and D).

Degrees of Similarity among Hausa dialects

It is observed that there are a higher percentage of similarities among eastern dialects than the western dialects. Various percentages of similarities in couples of dialects that range from 99.5% to 93% id further observed. This reflects a high degree of homogeneity among the dialects and a high degree of intelligibility among the dialects. It is observed that there are cases of couple (s) of dialects that belong to different group but yet they reflect a high percentage of similarities and in some other cases a couple or couples of dialects may belong to the same group but they reflect a high percentage of similarities and in some other cases a couple or couples of dialects or due to the high level of conservativeness of the speakers of the dialect (s). The time depth of the dialects stands between 27 and 405 years. Thus, in 2700 years if the degree of dissimilarities is constant and dialects will be completely different languages in the same family. The condition can be reverted if the speakers develop decide come together. The attitude of the speakers is a determinant factor in the dissimilarities or similarities of the dialects.

References

Adamu, M. (1970) The Hausa Factor in West Africa Zaria and Ibadan. A.B.U and OAU Presses.

Ahmed, U. and Daura, B. (1970) An Introduction to Classical Hausa and Major Dialects. Zaria NNPC.

Alkali, M. (1985) “Pilgrimage Tradition in Nigeria.”Annals of Borno Vol. II (1985).Pp. 1- 12.

Bagery, G.P. (1934) A Hausa-English Dictionary.Oxford University Press.Dauda, Bello (1979). “The Spread of Hausa in Yola and Maiduguri” Published M.A Dissertation, Department of Languages and Linguistics University of Maiduguri.

Bashir, M. Sambo (1999) “Comparative Analysis of Some Lexical Items in Kanuri and Teda”. Arts and Social Science Research Journal Nigerian Defence Academy Kaduna.

Bolinger D. (1975) Aspect of Language. Harcourt-Brace Inc. New York.

Brann, C.M.B. (1980) Mother Tongue, Other Tongue and Further Tongue University of Maiduguri

Dogo, A.M. (1977) “A Comparative Study of Kananci and Sakkwatanci”. Essay presented to the Department of Linguistics and Nigerian Languages. University of Ibadan.

Greenberg, J. (1963) “Some Universals of Language with particular Reference to the Order of Meaningful Elements”. In: Greenberg (ed) Universals of Languages C.U.P.

Greenberg, J. (1970) Languages of Africa. The Hague. Mouton.

Kidda M.A. (1977) “Comparative Lexical and Morphological Study of Dera and Tangale”. University of Maiduguri.

Kraft, C.H. and Kirk-Greene (1973) “Hausa, Teach Yourself Books”. African Linguistics 4 (973) 297:346.

Lemster, M. (1984) “Die Ausbreitum des Hausa in Nigeria in Jahrehundert “(The Spread of Hausa in Nigeria in the 20th C.). Unpublished M.A. Dissertation University of Toronto.

Muhammad, L. (SD) “Hausa Dialects”. Institute of Education.ABU Zaria.

Mohammed, UA (1990). “Sociolinguistic Situation of the Mixed Inner Area of Maiduguri Metropolitan: The Case Study of Hausari”. Unpublished Final year Essay. Department of Languages and Linguistics University of Maiduguri.

Newman, P. (1977) “Chadic Classification and Reconstruction”” Afro-Asiatic Linguistics 5(1) 1-42.

Onwubiko, K.B. (1967) History of West Africa. Onitsa, Africana Educational Publishers Nig. Ltd.

Salomone, F.A. (1975). “Becoming Hausa: Ethnic Pluralism and Stratication”. Africa (London) 453: 410-24.