ADEMOLA Kofoworola, educationist and children books author, known later in life as Lady Ademola, being wife of Adetokunbo Ademola, the first indigenous Chief Justice of Nigeria. Kofoworola was an early 20th Century symbol of educated elite, born 1914 to a lawyer father, Eric Moore, who was a member of the Colonial Legislative Council and who was trained in Middle Temple, London. Lady Ademola herself was taken to England at the age of 10 to school at C.M.S Girls’ School and Portway College in England. Thereafter, she became the first black African woman to enrol at Oxford University. After training as a teacher and having acquired other skills for a period of 11 years, she returned to Nigeria where she became a teacher at Queen’s College, Lagos. Later, she co-founded a school, and served as Headmistress to another. She became late in May 2002.

Origin

Kofoworola’s father, Eric Moore, was a Lagos lawyer of repute, and a member of the Legislative Council, to which he was nominated in 1915 before his election into the same role in 1934. Eric came from the Moore family, formerly named Odusina, of Ijemo. The Moores are a family of lawyers, clergymen and statesmen, well connected by marriage to many important families of the day. Kofoworola’s mother, Mrs. Aida Arabella Moore was a member of the Vaughan family. Her father was an Afro-Cherokee Indian from Camden, North Carolina in the U.S. and her mother was a Benin princess. Aida Moore’s grandfather, Scipio Vaughan, so named by his master, was born in Owu in c.1784. He was captured and sold into slavery in America in 1805, earning a living later by his iron-smelting and fashioning skills. On his deathbed he had requested his sons to return to Africa. Only two obeyed, with James, Kofoworola’s father, settling in Nigeria.

Places of Growth

Soon after her birth, Kofoworola’s family moved to Tinubu, a prestigious heart of Lagos where many of those who had achieved prominence in their professions lived. Ijemo, the name her father’s house in Tinubu was known by, was in reference to his homestead in Abeokuta. Soon after her third birthday she began school at CMS Girl’s Seminary, later proceeding to the primary school of the same organization. Kofoworola was often absent from school due to a recurring malaria. The severity of her illness in 1923 convinced her mother she is best schooling in England. In May 1924 she arrived in Plymouth with her mother and sister aboard the ship where she had celebrated her eleventh birthday. After a short delay, she joined many girls from the West African coast in the Portway College, a small private school in Reading where she enjoyed the tutelage of the charming Miss Kate Helen Jones, who taught the girls particularly how to be courtly.

Travels

In her Oxford days, Kofoworola broadened her knowledge of the British island, travelling wide whenever there was opportunity. In 1935 she returned home to a Lagos now dominated by Western culture. Some years later, she remarked there had been a significant swing to a marked African identity, with interesting personalities like Dr. Sapara who made the wearing of agbada buba popular, and Mrs. Jumoke Obasa who uniquely combined a western style jacket with Iro, championing the African Renaissance movement. Soon after her wedding, she went to Warri in company of her husband who as a judicial officer had been transferred there. In Warri, she founded a literary club where she engaged enthusiastic young people in scholarly and entertaining activities till her husband’s redeployment in 1946. Subsequently, Kofo followed her husband to many parts of the country where he was posted. When she arrived in Ibadan in 1953 she was invited to join the Western Regional Directorship the British Red Cross Society.

Relationship

Childhood

Kofoworola’s childhood was uneventful but happy; a large part of it being the Christ Church in Marina, near her home in Tinubu. Her devoutly Christian family walked down to the church on Sunday mornings and said prayers together by five in the morning and eight in the evening. Christmases entailed a plethora of activities for children. Festive occasions heralded the colorful outing of conjurers, masquerades, and acrobats from Olowogbowo area and from the Brazilian quarters of Lafiaji. Books formed an important part of Kofoworola’s upbringing and her father who often entertained her with stories of his studentship abroad, also read to her in bed.

Family

Kofoworola’s parents, Eric Moore and Aida Vaughan met through Eric’s sisters and they were married in Lagos in 1905. She was the second daughter and the third child of the family. In 1937 she was engaged to Tokunbo, son of Ladapo Ademola, whose acquaintance she had made as a child before going to England. They were married at the Cathedral Church of Christ in Lagos almost two years later and raised two sons and daughters. Ronke, the first, worked with Shell in Lagos, and was honored with the traditional title of the Iyalode of Ake.

Affiliates

Kofoworola involved herself in public and welfare duties in places of her husband’s assignment. In Warri, she participated in the founding of the Nigerian Council of Women Societies. On her return to Lagos, she served in the advisory committee of Farm Craft Centre, an institution where blind farmers were trained. She was also a member of the Federal Scholarship Selection Board as she is a lively member of the Young Women’s Christian Association[1].

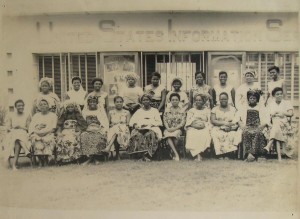

Contemporaries

Miss Perham was one who advised Kofoworola to start out with what she really wanted to do when she was to choose between law and teaching. Perham had met the family in Lagos during a visit and she would become in the UK a valued friend and mentor. She is known to history as an authority on Indirect Rule in Africa, and editor of Lord Lugard’s diaries. One of Kofoworola’s students at Queen’s College was Fola Akintunde (later Mrs. Ighodalo) who became Permanent Secretary in Oyo State. Mrs Joke Coker who later became the first Nigerian principal of the school was also a contemporary. Earlier at Portway College, Kofoworola had made acquaintance of children of eminent Lagosians, some of who charted their own course of distinction in life. Examples were Stella Thomas, Titi Pearse who became Mrs. Shodehinde, and her sister, Dupe Pearse. She also met Ayo Adeniji-Jones, Flora and Toke Doherty, Getunde Shyngle, Ronke Macaulay, Ayo George who became Lady Alakija, Alaba, and Molara Williams.

Education

Evidently, Kofoworola got the best of lifelong education from Portway College, which proved to be a home away from home in Britain. For her undergraduate studies, she was in Sheffield for one year preparatory course before settling at Oxford. Although she was not opposed to the idea of taking after her father in his legal profession, she did eventually went for the arts. Kofoworola went to St. Hughes College, University of Oxford, UK and graduated in 1935 after three years of study in History, English, and French.

Tutor

Some months after returning to Nigeria in 1936, Kofoworola joined the Queen’s College Lagos as tutor of English and Civics in senior classes. She became Headmistress of a school she co-founded in Lagos, New Era Girl’s Secondary School. Another school, Girls’ Secondary Modern School was co-founded by her in Lagos. She worked as a teacher in Warri College in the 1940s. She was the first female director and former chairman, Board of Trustees of the United Bank for Africa[2].

Motivation

Being privy to a good British education, she was inspired to replicate the same in her country home. The courage to choose teaching, apparently had come from her mentor, Perham, and the memory of dedicated tutors like Miss Kate Helen Jones of the Portway College who unfortunately became late in her class’s final year may have formed for her an opinion about the girl child and community development. In an address made at a seminar for African women at the University College of Ibadan she had she advocated a “new concept for leadership which would absorb the high sense of community responsibility inherent in African women.”

Accomplishments

Kofoworola authored many children’s books. Her tales, usually punctuated with songs, focus on teaching basic moral lessons. She also involved herself in gender activism and with the Red Cross, hence earning international acclaim. She was honoured in 1958 with the Member of Order of the British Empire and by Tafa Balewa’s government with the OFR. She took the traditional titles of the Mojibade of Ake, and Lika of Ijemo. Her first-hand account of her experiences in Britain of the 1930s was published in Ten Africans, a 1936 collection edited by colonial expert, Margery Perham. There were no experiences of racism in Kofoworola’s account, except that her cleverness was to her irritation, often met with surprise.

[1] Nigerian Heroes, Folarin Coker, CSS Bookshop Limited, Lagos, 2008 pg 49

[2] Newswatch Who’s Who in Nigeria, Nyaknno Osso, Newswatch Communications Limited, Ikeja, 1990, pg. 51